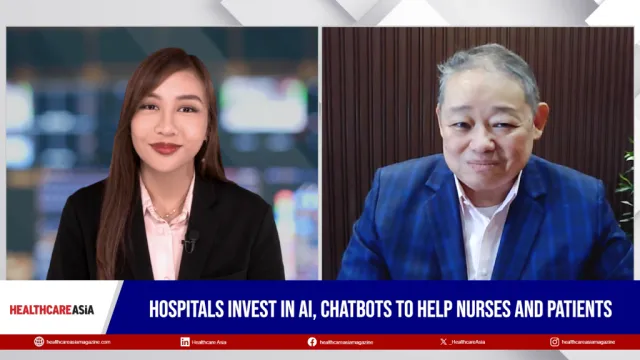

Public and private sector collaboration key in providing universal health care across APAC

Many private-public partnerships are still not designed to help the masses, only niche segments.

An alignment between Asia Pacific’s (APAC) public and private sectors could be the key to fully achieving universal health care (UHC) across the region which is in line with the United Nations’ (UN) goal of achieving ‘health for all’ by 2030, according to KPMG.

However, this seems easier said than done given the disconnect between the two sectors in terms of workforce, spending and ideals.

“Whilst the benefits of alignment between public and private sectors for universal health care, UHC purposes can be quite compelling, the scale of technical and resource challenges is enormous,” KPMG said. It also noted how challenges including data transparency between public and private sectors make the realisation of health economics much more difficult to both predict and achieve.

Also read: Korea, Indonesia collaborate to implement universal health insurance program

The private sector is considered as a leader in developing future care models that can expand on the back of technological advancements, whilst public players are increasingly taking a dominant position in low and middle-income countries implementing UHC, the report highlighted.

“An analysis by Stenberg and colleagues showed that the annual health spending gap across 67 low and middle-income countries is around US$300b,” KPMG highlighted in its report. “And according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there is a shortfall of some 17 million people in the global health workforce, mostly in Asia, Africa and the Middle East.”

In addition, the scale of private health services is also too large for governments to ignore, the report stated. In a study looking at 77 low and middle-income countries, more than 50% of the population would choose a private provider as their first choice for basic care.

“Many private-public partnerships (PPPs) are still not designed to help the masses, only niche segments,” Sysmex Asia Pacific CEO Frank Buescher said in the report, citing that policymakers need to differentiate between cost savings and cost efficiencies.

Meanwhile, political momentum behind UHC is now at an all-time high, with governments around the world making major financial commitments toward UHC and many national leaders also grasping its political value at the ballot box, according to KPMG.

Also read: Malaysia proposes 7.8% larger 2019 budget of US$6.9b for healthcare

According to the report, this represents both a threat and an opportunity for the private sector given that the proportion of self-paying and privately-insured patients may decline as a result of well-designed and publicly funded UHC programs.

“The share of spending from out-of-pocket and pre-paid private sources is also projected to fall or at best remain flat over the next two decades,” the firm said in the report.

On the other hand, the comparably stronger growth in public spending could represent an unprecedented opportunity.

“A World Bank study on 24 UHC reforms in developing countries found that the annual spend on national programs can be as high as 6.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in some countries,” KPMG said in its report. “In Indonesia, for example, some 60% of the US$6b budget is earmarked to cover the provision of services by private hospitals enlisted in the nation’s NHI scheme.”

The goal is not to replace healthcare provision but to work together, in terms of augmenting operations at clinics, inventory control and even using smart chips, Dr. Hsien-Hsien Lei, Asia Pacific (APAC) vice president of medical and scientific affairs at Medtronic, reiterated in the report. “Medtech needs to link to the overall government digital transformation program, for instance the interoperability of databases.”

In Asia, Thailand is a trailblazer for UHC success thanks to a series of incremental reforms implemented to health financing over the last 15 years. “Under the UHC scheme introduced in 2002, the government consolidated welfare revenue streams to cover nearly 48 million people, automated the enrollment process to avoid the pitfalls of means testing and introduced a 2% levy on tobacco and alcohol sales to strengthen preventative and primary care,” KPMG noted.

These funding shifts have enabled Thailand to fund more than 700 new healthcare initiatives to date.

Also read: Higher insurance coverage to boost Vietnam's healthcare sector

Likewise, Delhi’s Mohalla clinics are further examples of a government forging practical ties with the private sector to provide care for the underserved population.

Since 2015, 164 Mohalla clinics have been set up across the region with plans to reach 1000 such facilities by the end of 2018. The clinics are made from used shipping containers and each can see up to 100 patients per day with costs fully shouldered by the government. The clinics also serve as a supplemental income source for private doctors.

“The model is now being rolled out to other states in India, with plans for 200 clinics in Hyderabad,” KPMG highlighted.

In the journey towards health for all, universal health care (UHC) countries should seek balance between control and risk, affordability and innovation, and competition and consistency. In line with every country pursuing UHC by 2030, the report proposed solutions that could further guide public and private sector collaboration that includes establishing a global network of private sector players to share lessons on sustainable models of health promotion and cross-train the workforce and installing a neutral mediation service to improve dialogue between public and private sector organisations.

As well, it proposed documenting a UHC readiness checklist assessment compromising of timely payment mechanisms, independent quality accreditation, price determination and workforce standardisation.

Advertise

Advertise