Why Thailand is pressed to revamp healthcare

Analysts are bracing themselves for a gradual release of reforms soon.

The government is aware of the financial cracks on its highly praised universal healthcare coverage, but analysts expect reforms to come out in a trickle whilst the country remains in a delicate political climate.

When one of roughly 50 million Thai citizens covered by the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) steps into a district hospital to receive medical consultation or treatment, the experience is pleasant and affordable due to the generous free coverage on curative and rehabilitation services. But for how long this can be sustained is becoming increasingly in question as Thailand hurtles towards an ageing population and soaring healthcare costs.

One of the most pressing policy challenges for the Thai healthcare system is identifying new sources of funding and reducing nonessential outpatient elements within the benefit package, whilst still safeguarding admission services and continuity of treatment for chronic conditions, says Viroj Tangcharoensathien, senior advisor, international health policy program, ministry of public health in Thailand and the secretary general of the International Health Policy Program Foundation.

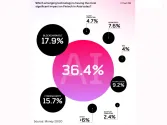

He warns that the healthcare system is over reliant on general taxation as the main source of funding for the Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS). This puts the national healthcare insurance scheme at risk of incurring shortfalls, especially during cyclical economic downturns and structural adjustments. Allianz Worldwide Care estimates that UCS covers roughly 50 million people or 76% of Thailand’s population, CSMBS at 7%, and the Worker Compensation Scheme and the Social Security Scheme (SSS) covering 15%, with domestic private insurance schemes available for employees of large companies. Schemes funded through general taxation will be at the top of the government reform list, says Wei Zheng Ang, pharmaceuticals & healthcare analyst at BMI Research, but changes will likely be introduced gradually due to the complex web of diverse stakeholder interests.

Doctors in the country have been calling for a co-payment scheme to the UCS, but Wei reckons such a measure would remain in limbo due to concerns that it will make it harder for lower-income patients to avail healthcare services. Despite declining inequality in the past decades, there were 7.1 million impoverished people in Thailand and an additional 6.7 million living within 20% above the national poverty line, according to the World Bank.

Raising low reimbursements

Bolstering support for private hospitals is one key improvement that could be expected. The low rate of reimbursements punished several private hospitals last year, prompting the Social Security Office (SSO) to promise an increased budget moving forward. Analysts expect the SSO to raise the reimbursement rates for the SSS. “There were a number of private hospitals, unable to cope with the cost of medical services under the SSS, that have exited the social security system in FY16 — implying unrealistic reimbursement rates for the SSS,” says Apichaya Ketruttanaborvorn, analyst at DBS. “We assign a high probability that the SSO will increase its reimbursement rates for its member hospitals in FY17F.”

The SSO will likely push through with the reimbursement increase based on historical trends. The SSO adjusts its reimbursement rates every two years, and the current rate was revised in 2014. Ketruttanaborvorn estimates the rate of increase will likely be the same quantum as the healthcare inflation rate, or in the range of 4-5%. “The SSS reimbursement rate normally tracks the inflation and the growing size of the fund under the SSS,” she explains. “This should alleviate concerns over the decreasing number of member hospitals which might not be able to meet the growing healthcare demand under the SSS.”

Should the reimbursement increase push through, hospitals with a sizeable revenue exposure to the SSS will be the big winners. This includes Chularat Hospital, a private healthcare provider covering the eastern part of Bangkok and nearby provinces, which has a large SSS exposure of 45% and has more than 145,000 registered SSS patients in FY17F. It will also benefit Ladprao General Hospital, a private healthcare provider targeting mid-income patients in Bangkok, which has 171,000 registered SSS patients. Another winner could be the Bangkok Chain Hospital, a hospital chain operator that focuses on middle-income patients and also runs one premium hospital, which had 762,000 registered SSS patients as of the third quarter of last year.

Funding elderly care

Healthcare demand will skyrocket as Thailand hurtles towards a rapidly ageing population. The World Bank estimates that 11% of the country’s population, or around 7.5 million people, are 65 years or older, more than doubling from the 5% in 1995. Dr Zhanming Liang, senior lecturer at La Trobe University, and Dr Phudit Tejativaddhana, professor at Naresuan University, have published a study warning about the financial pressures an increasingly elderly population in Thailand would bring to the healthcare system. Currently, the old age dependency rate — or the number of people aged 65 and above per 100 population aged 15 to 64 — is at a relatively low 13%, but it is predicted to quadruple to 53.1% in 2050.

With more elderly citizens, many of whom will require treatment and care for chronic diseases, Thailand’s universal health coverage will come under pressure. Providing these costly healthcare services for free as the country’s tax base thins will likely put a lot of strain on the public coffers. “Achieving universal health insurance has certainly made Thailand proud. However, the complex three-tier health insurance arrangements together with the increasing healthcare needs threaten its sustainability,” they say, expecting a spike in healthcare service demand but also a decrease in tax contributions from retirees.

Factoring in the more than 60% of the population working in the informal sector, a segment that may not be subject to tax contributions, it becomes clear that the government must pursue a more sustainable solution than simply hiking up taxes, say Liang and Tejativaddhana.

The forecasted jump in elderly population and large swathes of informal workers “make significant increases of tax revenue by the Thai Government impossible in the long run, at least not at a rate that can match the increasing healthcare demands,” they say. “Significant injection into healthcare expenditure to meet the increasing demand alone is not a feasible solution in Thailand. Efforts to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of service delivery are strongly recommended.” Thai health and social welfare systems need to start preparing long-term care policies, reckons Tangcharoensathien. “This will require adapting sources of finance and modalities of care, and developing more effective interface mechanisms between families and community care organisations, and between health and other social services,” he says.

Addressing healthcare gap

Increasing funding for Thailand’s healthcare system should also help address the troubling healthcare gap between Bangkok and Tier 2 cities — namely Chiang Mai, Khon Kaen, Surat Thani, Ubon Ratchathani, Nakhon Ratchasima, Chonburi, and Songkhla. Tier 2 cities face an alarming shortage of medical specialists such as physicians, surgeons, and anesthesiologists, reckons Sittichai Duangrattanachaya, healthcare analyst at Maybank Kim Eng Thailand. In 2014, Bangkok had an estimated one doctor per 1,075 people and one nurse per 285 — 59% and 49% better, respectively, than in Tier 2 cities. Moreover, Bangkok had 3.7 beds per 1,000 people, 54% better than in Tier 2 cities.

“Considering population structure and medical school attendants, shortage in the number of physicians will surge due to ageing population,” says Mickaeil.

Advertise

Advertise